Pell number

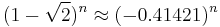

In mathematics, the Pell numbers are an infinite sequence of integers that have been known since ancient times, the denominators of the closest rational approximations to the square root of 2. This sequence of approximations begins 1/1, 3/2, 7/5, 17/12, and 41/29, so the sequence of Pell numbers begins with 1, 2, 5, 12, and 29. The numerators of the same sequence of approximations are half the companion Pell numbers or Pell-Lucas numbers; these numbers form a second infinite sequence that begins with 2, 6, 14, 34, and 82.

Both the Pell numbers and the companion Pell numbers may be calculated by means of a recurrence relation similar to that for the Fibonacci numbers, and both sequences of numbers grow exponentially, proportionally to powers of the silver ratio 1 + √2. As well as being used to approximate the square root of two, Pell numbers can be used to find square triangular numbers, to construct integer approximations to the right isosceles triangle, and to solve certain combinatorial enumeration problems.[1]

As with Pell's equation, the name of the Pell numbers stems from Leonhard Euler's mistaken attribution of the equation and the numbers derived from it to John Pell. The Pell-Lucas numbers are also named after Édouard Lucas, who studied sequences defined by recurrences of this type; the Pell and companion Pell numbers are Lucas sequences.

Contents |

Pell numbers

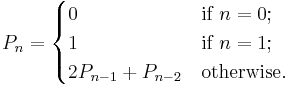

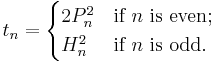

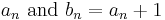

The Pell numbers are defined by the recurrence relation

In words, the sequence of Pell numbers starts with 0 and 1, and then each Pell number is the sum of twice the previous Pell number and the Pell number before that. The first few terms of the sequence are

The Pell numbers can also be expressed by the closed form formula

For large values of n, the  term dominates this expression, so the Pell numbers are approximately proportional to powers of the silver ratio

term dominates this expression, so the Pell numbers are approximately proportional to powers of the silver ratio  , analogous to the growth rate of Fibonacci numbers as powers of the golden ratio.

, analogous to the growth rate of Fibonacci numbers as powers of the golden ratio.

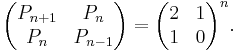

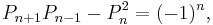

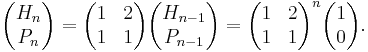

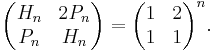

A third definition is possible, from the matrix formula

Many identities can be derived or proven from these definitions; for instance an identity analogous to Cassini's identity for Fibonacci numbers,

is an immediate consequence of the matrix formula (found by considering the determinants of the matrices on the left and right sides of the matrix formula).[2]

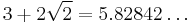

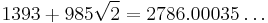

Approximation to the square root of two

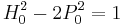

Pell numbers arise historically and most notably in the rational approximation to the square root of 2. If two large integers x and y form a solution to the Pell equation

then their ratio  provides a close approximation to

provides a close approximation to  . The sequence of approximations of this form is

. The sequence of approximations of this form is

where the denominator of each fraction is a Pell number and the numerator is the sum of a Pell number and its predecessor in the sequence. That is, the solutions have the form  . The approximation

. The approximation

of this type was known to Indian mathematicians in the third or fourth century B.C.[3] The Greek mathematicians of the fifth century B.C. also knew of this sequence of approximations;[4] they called the denominators and numerators of this sequence side and diameter numbers and the numerators were also known as rational diagonals or rational diameters.[5]

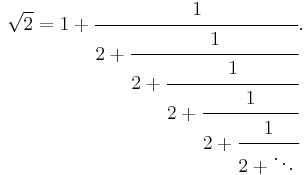

These approximations can be derived from the continued fraction expansion of  :

:

Truncating this expansion to any number of terms produces one of the Pell-number-based approximations in this sequence; for instance,

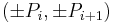

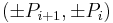

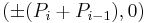

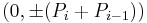

As Knuth (1994) describes, the fact that Pell numbers approximate  allows them to be used for accurate rational approximations to a regular octagon with vertex coordinates

allows them to be used for accurate rational approximations to a regular octagon with vertex coordinates  and

and  . All vertices are equally distant from the origin, and form nearly uniform angles around the origin. Alternatively, the points

. All vertices are equally distant from the origin, and form nearly uniform angles around the origin. Alternatively, the points  ,

,  , and

, and  form approximate octagons in which the vertices are nearly equally distant from the origin and form uniform angles.

form approximate octagons in which the vertices are nearly equally distant from the origin and form uniform angles.

Primes and squares

A Pell prime is a Pell number that is prime. The first few Pell primes are

- 2, 5, 29, 5741, ... (sequence A086383 in OEIS).

As with the Fibonacci numbers, a Pell number  can only be prime if n itself is prime.

can only be prime if n itself is prime.

The only Pell numbers that are squares, cubes, or any higher power of an integer are 0, 1, and 169 = 132.[6]

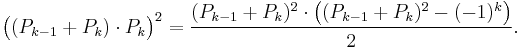

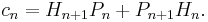

However, despite having so few squares or other powers, Pell numbers have a close connection to square triangular numbers.[7] Specifically, these numbers arise from the following identity of Pell numbers:

The left side of this identity describes a square number, while the right side describes a triangular number, so the result is a square triangular number.

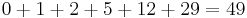

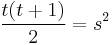

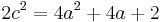

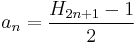

Santana and Diaz-Barrero (2006) prove another identity relating Pell numbers to squares and showing that the sum of the Pell numbers up to  is always a square:

is always a square:

For instance, the sum of the Pell numbers up to  ,

,  , is the square of

, is the square of  . The numbers

. The numbers  forming the square roots of these sums,

forming the square roots of these sums,

- 1, 7, 41, 239, 1393, 8119, 47321, ... (sequence A002315 in OEIS),

are known as the Newman–Shanks–Williams (NSW) numbers.

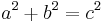

Pythagorean triples

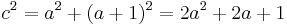

If a right triangle has integer side lengths a, b, c (necessarily satisfying the Pythagorean theorem a2+b2=c2), then (a,b,c) is known as a Pythagorean triple. As Martin (1875) describes, the Pell numbers can be used to form Pythagorean triples in which a and b are one unit apart, corresponding to right triangles that are nearly isosceles. Each such triple has the form

The sequence of Pythagorean triples formed in this way is

- (4,3,5), (20,21,29), (120,119,169), (696,697,985), ....

Pell-Lucas numbers

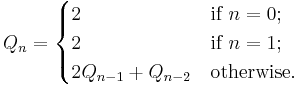

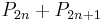

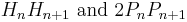

The companion Pell numbers or Pell-Lucas numbers are defined by the recurrence relation

In words: the first two numbers in the sequence are both 2, and each successive number is formed by adding twice the previous Pell-Lucas number to the Pell-Lucas number before that, or equivalently, by adding the next Pell number to the previous Pell number: thus, 82 is the companion to 29, and 82 = 2 * 34 + 14 = 70 + 12. The first few terms of the sequence are (sequence A002203 in OEIS): 2, 2, 6, 14, 34, 82, 198, 478...

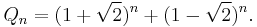

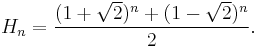

The companion Pell numbers can be expressed by the closed form formula

These numbers are all even; each such number is twice the numerator in one of the rational approximations to  discussed above.

discussed above.

Computations and connections

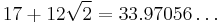

The following table gives the first few powers of the silver ratio  and its conjugate

and its conjugate  .

.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 0 |  |

|

| 1 |  |

|

| 2 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

| 4 |  |

|

| 5 |  |

|

| 6 |  |

|

| 7 |  |

|

| 8 |  |

|

| 9 |  |

|

| 10 |  |

|

| 11 |  |

|

| 12 |  |

|

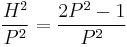

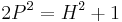

The coefficients are the Half companion Pell numbers  and The Pell numbers

and The Pell numbers  which are the (non-negative) solutions to

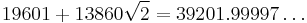

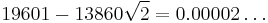

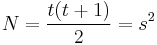

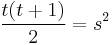

which are the (non-negative) solutions to  . A Square triangular number is a number

. A Square triangular number is a number  which is both the

which is both the  th triangular number and the

th triangular number and the  th square number. A near isosceles Pythagorean triple is an integer solution to

th square number. A near isosceles Pythagorean triple is an integer solution to  where

where  .

.

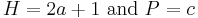

The next table shows that splitting the odd number  into nearly equal halves gives a square triangular number when n is even and a near isosceles Pythagorean triple when n is odd. All solutions arise in this manner.

into nearly equal halves gives a square triangular number when n is even and a near isosceles Pythagorean triple when n is odd. All solutions arise in this manner.

|

|

|

t | t+1 | s | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 17 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 6 | |||

| 5 | 41 | 29 | 20 | 21 | 29 | |||

| 6 | 99 | 70 | 49 | 50 | 35 | |||

| 7 | 239 | 169 | 119 | 120 | 169 | |||

| 8 | 577 | 408 | 288 | 289 | 204 | |||

| 9 | 1393 | 985 | 696 | 697 | 985 | |||

| 10 | 3363 | 2378 | 1681 | 1682 | 1189 | |||

| 11 | 8119 | 5741 | 4059 | 4060 | 5741 | |||

| 12 | 19601 | 13860 | 9800 | 9801 | 6930 |

Definitions

The half companion Pell Numbers  and the Pell numbers

and the Pell numbers  can be derived in a number of easily equivalent ways:

can be derived in a number of easily equivalent ways:

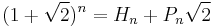

Raising to powers:

From this it follows that there are closed forms:

and

Paired recurrences:

and matrix formulations:

So

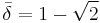

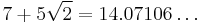

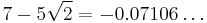

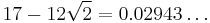

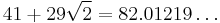

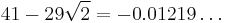

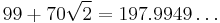

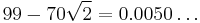

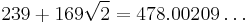

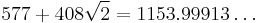

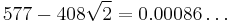

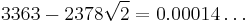

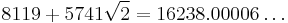

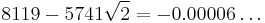

Approximations

The difference between  and

and  is

is  which goes rapidly to zero. So

which goes rapidly to zero. So  is extremely close

is extremely close  .

.

From this last observation it follows that the integer ratios  rapidly approach

rapidly approach  while

while  and

and  rapidly approach

rapidly approach  .

.

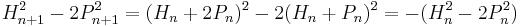

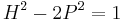

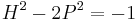

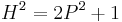

H2 − 2P2 = ±1

Since  is irrational, we can't have

is irrational, we can't have  i.e.

i.e.  . The best we can achieve is either

. The best we can achieve is either  or

or  .

.

The (non-negative) solutions to  are exactly the pairs

are exactly the pairs  even and the solutions to

even and the solutions to  are exactly the pairs

are exactly the pairs  odd. To see this, note first that

odd. To see this, note first that

so that these differences, starting with  are alternately

are alternately  . Then note that every positive solution comes in this way from a solution with smaller integers since

. Then note that every positive solution comes in this way from a solution with smaller integers since  . The smaller solution also has positive integers with the one exception

. The smaller solution also has positive integers with the one exception  which comes from

which comes from  .

.

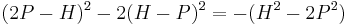

Square triangular numbers

The required equation  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  which becomes

which becomes  with the substitutions

with the substitutions  . Hence the nth solution is

. Hence the nth solution is  and

and

Observe that  and

and  are relatively prime so that

are relatively prime so that  happens exactly when they are adjacent integers, one a square

happens exactly when they are adjacent integers, one a square  and the other twice a square

and the other twice a square  . Since we know all solutions of that equation, we also have

. Since we know all solutions of that equation, we also have

and

This alternate expression is seen in the next table.

|

|

|

t | t+1 | s | a | b | c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 49 | 50 | 35 | 21 | 20 | 29 | ||

| 4 | 17 | 12 | 288 | 289 | 204 | 119 | 120 | 169 | ||

| 5 | 41 | 29 | 1681 | 1682 | 1189 | 697 | 696 | 985 | ||

| 6 | 99 | 70 | 9800 | 9801 | 6930 | 4059 | 4060 | 5741 |

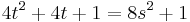

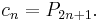

Pythagorean triples

The equality  occurs exactly when

occurs exactly when  which becomes

which becomes  with the substitutions

with the substitutions  . Hence the nth solution is

. Hence the nth solution is  and

and

The table above shows that, in one order or the other,  are

are  while

while

Notes

- ^ For instance, Sellers (2002) proves that the number of perfect matchings in the Cartesian product of a path graph and the graph K4-e can be calculated as the product of a Pell number with the corresponding Fibonacci number.

- ^ For the matrix formula and its consequences see Ercolano (1979) and Kilic and Tasci (2005). Additional identities for the Pell numbers are listed by Horadam (1971) and Bicknell (1975).

- ^ As recorded in the Shulba Sutras; see e.g. Dutka (1986), who cites Thibaut (1875) for this information.

- ^ See Knorr (1976) for the fifth century date, which matches Proclus' claim that the side and diameter numbers were discovered by the Pythagoreans. For more detailed exploration of later Greek knowledge of these numbers see Thompson (1929), Vedova (1951), Ridenhour (1986), Knorr (1998), and Filep (1999).

- ^ For instance, as several of the references from the previous note observe, in Plato's Republic there is a reference to the "rational diameter of 5", by which Plato means 7, the numerator of the approximation 7/5 of which 5 is the denominator.

- ^ Pethő (1992); Cohn (1996). Although the Fibonacci numbers are defined by a very similar recurrence to the Pell numbers, Cohn writes that an analogous result for the Fibonacci numbers seems much more difficult to prove. (However, this was proven in 2006 by Bugeaud et al.)

- ^ Sesskin (1962). See the square triangular number article for a more detailed derivation.

References

- Bicknell, Marjorie (1975). "A primer on the Pell sequence and related sequences". Fibonacci Quarterly 13 (4): 345–349. MR0387173.

- Cohn, J. H. E. (1996). "Perfect Pell powers". Glasgow Mathematical Journal 38 (1): 19–20. doi:10.1017/S0017089500031207. MR1373953.

- Dutka, Jacques (1986). "On square roots and their representations". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 36 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1007/BF00357439. MR0863340.

- Ercolano, Joseph (1979). "Matrix generators of Pell sequences". Fibonacci Quarterly 17 (1): 71–77. MR0525602.

- Filep, László (1999). "Pythagorean side and diagonal numbers". Acta Mathematica Academiae Paedagogiace Nyíregyháziensis 15: 1–7. http://www.emis.de/journals/AMAPN/vol15/filep.pdf.

- Horadam, A. F. (1971). "Pell identities". Fibonacci Quarterly 9 (3): 245–252, 263. MR0308029.

- Kilic, Emrah; Tasci, Dursun (2005). "The linear algebra of the Pell matrix". Boletín de la Sociedad Matemática Mexicana, Tercera Serie 11 (2): 163–174. MR2207722.

- Knorr, Wilbur (1976). "Archimedes and the measurement of the circle: A new interpretation". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 15 (2): 115–140. doi:10.1007/BF00348496. MR0497462.

- Knorr, Wilbur (1998). ""Rational diameters" and the discovery of incommensurability". American Mathematical Monthly 105 (5): 421–429. doi:10.2307/3109803. JSTOR 3109803.

- Knuth, Donald E. (1994). "Leaper graphs". The Mathematical Gazette 78 (483): 274–297. arXiv:math.CO/9411240. doi:10.2307/3620202. JSTOR 3620202.

- Martin, Artemas (1875). "Rational right angled triangles nearly isosceles". The Analyst 3 (2): 47–50. doi:10.2307/2635906. JSTOR 2635906.

- Pethő, A. (1992). "The Pell sequence contains only trivial perfect powers". Sets, graphs, and numbers (Budapest, 1991). Colloq. Math. Soc. János Bolyai, 60, North-Holland. pp. 561–568. MR1218218.

- Ridenhour, J. R. (1986). "Ladder approximations of irrational numbers". Mathematics Magazine 59 (2): 95–105. doi:10.2307/2690427. JSTOR 2690427.

- Santana, S. F.; Diaz-Barrero, J. L. (2006). "Some properties of sums involving Pell numbers". Missouri Journal of Mathematical Sciences 18 (1). http://www.math-cs.cmsu.edu/~mjms/2006.1/diazbar.pdf.

- Sellers, James A. (2002). "Domino tilings and products of Fibonacci and Pell numbers". Journal of Integer Sequences 5. MR1919941. http://www.emis.de/journals/JIS/VOL5/Sellers/sellers4.pdf.

- Sesskin, Sam (1962). "A "converse" to Fermat's last theorem?". Mathematics Magazine 35 (4): 215–217. doi:10.2307/2688551. JSTOR 2688551.

- Thibaut, George (1875). "On the Súlvasútras". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal 44: 227–275.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1929). "III.—Excess and defect: or the little more and the little less". Mind: New Series 38 (149): 43–55. JSTOR 2249223.

- Vedova, G. C. (1951). "Notes on Theon of Smyrna". American Mathematical Monthly 58 (10): 675–683. doi:10.2307/2307978. JSTOR 2307978.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Pell Number" from MathWorld.